The spread of coronavirus within the UK has picked up pace in recent days.

The number of reported cases passed 500 on March 12, 1,000 on March 14, 2,000 on March 18, and 5,000 on March 21.

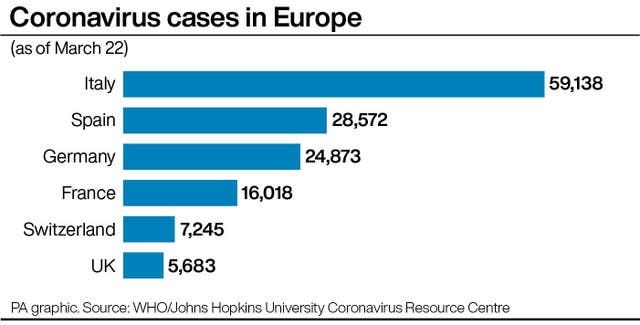

How does the UK currently compare with some of its closest European neighbours?

– Number of cases and deaths

As of March 22, the UK had 5,683 recorded cases of coronavirus. A simple comparison with other countries shows that this is currently the sixth highest number in Europe, behind Italy (59,138), Spain (28,572), Germany (24,873), France (16,018) and Switzerland (7,245).

The UK has the fourth highest number of coronavirus-related deaths in Europe. The figure stood at 281 as of March 22, behind Italy (5,476), Spain (1,720) and France (674).

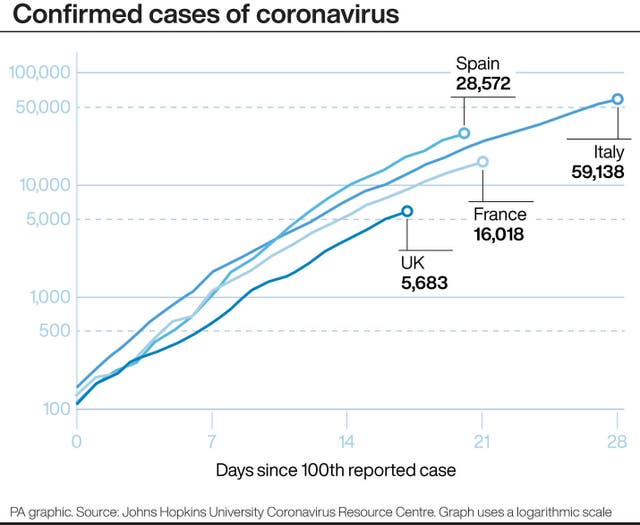

These numbers can be put into context by looking at how they have changed over time and examining how they compare against each other.

However, there are risks in making these sorts of calculations, firstly when considering mortality rates.

– Mortality rates

Dividing the number of reported cases of coronavirus by the number of coronavirus-related deaths gives an approximate mortality rate for each country – but these figures should be treated with caution.

This is because different countries are testing a different range of people and at different scales. In the UK, people with the virus who are self-isolating at home are not being tested, while those being tested are mainly people with underlying health symptoms or who are already in hospital. Other countries – such as Germany – are testing a greater volume of their population, and this has an impact on the overall mortality rate.

The latest figures put the UK’s mortality rate at around 5%, with Italy at 9% and Germany at 0.4%. But this sort of variation is to be expected at such an early stage of the outbreak, particularly with only a limited amount of data available and with countries following different testing policies.

Here in the UK most mild cases of the virus are not being included in the number of reported cases. Testing more patients would increase the “denominator” – the number of people who have a positive coronavirus test. For a given number of deaths, this is likely to have the effect of pushing down the mortality rate, according to Duncan Young, professor of intensive care medicine at Oxford University.

He suggests an alternative approach might be to compare death rates for cases of equal severity – for example, patients in Italy and the UK who show the same level of sickness when admitted to hospital or an intensive care unit. Were these figures available, Prof Young says they might give “a very crude estimate of the quality/overload of the care system. Any difference could, however, also be due to differences in patient characteristics (age, smoking status) between UK and Italy”.

– Evolution of outbreak

Another way of measuring the UK against Europe is to consider the evolution of the outbreak and see whether the country is mirroring the trend of another country – possibly by a particular number of days or weeks.

On March 7, the number of reported cases in Italy was 5,883 – similar to the number of reported cases in the UK on March 22 (5,683).

The number of coronavirus-related deaths in Italy on March 7 was 233 – again, similar to the number for the UK on March 22 (281).

The figures suggest the UK seems to be running around two weeks behind Italy and might therefore reach the equivalent number of cases and deaths in a fortnight.

But while the evolution of the outbreak in the UK – as measured by confirmed cases – is broadly following the same shape as that in Italy, it is impossible to predict if the trajectory will be identical. Overall numbers might be masking important differences in the ages of coronavirus cases and victims, as well as the difference in testing regimes, all of which might influence the pace and scope of the outbreak’s development in the UK over the next few weeks.

– Age of victims

Professor Sheila Bird, former programme leader of the Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit at the University of Cambridge, suggests another approach: aligning countries on the basis of the evolution of the outbreak and then, for each age group, comparing the number of deaths per million of population.

“The starkness of the increase in relative death rates by age group that we have seen in other countries is why the UK seeks to protect those aged over 70 years from becoming exposed to Covid-19,” she says.

Based on 1,625 deaths in Italy, and considering the age distribution of the Italian population, Prof Bird found that death rate per million of population appears to be “four times higher at 50-59 years than at 40-49 years; 19 times higher at 60-69 years; 105 times higher per million of population at 70-79 years than at 40-49 years; and around 210 times higher per million of population at 80-plus years than at 40-49 years.”

She notes that in “just a few weeks, sadly, the UK will be able to estimate these rates for its own population” – which will then help give a more detailed picture of how the UK compares with some of its European neighbours.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here