A new mRNA cancer vaccine made by pharmaceutical firm Moderna is being trialled in British patients.

The mRNA technology – which was adapted to make Covid-19 jabs – works by helping the body recognise and fight cancer cells.

Experts believe these vaccines may lead to a new generation of “off-the-shelf” cancer therapies.

Once in the body, the mRNA (a genetic material) ‘teaches’ the immune system how cancer cells differ to healthy cells and mobilises it to destroy them.

mRNA cancer vaccines from firms like BioNTech, Merck and Moderna have been undergoing testing in small trials across the globe, with promising results.

In some cases, vaccines are created specifically for the patient in the lab using their own genetic information, while others are more general vaccines targeted at specific types of cancer.

In the latest development, British patients are trialling a vaccine called mRNA-4359 as part of an early-stage clinical trial that will initially look at safety as well as effectiveness.

The vaccine is aimed at people with advanced melanoma, lung cancer and other solid tumour cancers.

An 81-year-old man, who is taking part in the trial arm run by Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, was the first UK person to receive the vaccine at Hammersmith Hospital in late October.

The man, from Surrey, who does not wish to be named, has malignant melanoma skin cancer which is not responding to treatment.

He said: “I had a different immunotherapy, I had radiotherapy, the only thing I didn’t have was chemotherapy. So, the options were either do nothing and wait, or get involved and do something.

“I’m extremely grateful to the hospitals and the individuals that are running these trials.

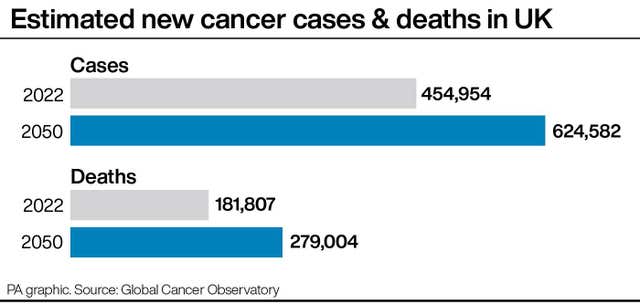

“Somehow we have to change the fact that one in every two people get cancer at some point, and we have to make the odds better.”

During the trial, the vaccine will be tested alone and in combination with an existing drug pembrolizumab, which is an approved immunotherapy treatment, also known as Keytruda.

Between 40 and 50 patients are being recruited across the globe for the trial, known as Mobilize, including in London, Spain, the US and Australia, although it could be expanded.

Dr Kyle Holen, head of development, therapeutics and oncology at Moderna, told the PA news agency the vaccine may be able to treat a range of cancers.

He said: “We currently are studying both melanoma patients and lung cancer patients, but we believe that there’s an opportunity for this vaccine in the Mobilize trial to treat many other cancers.

“We believe it could be effective in head-neck cancer, we believe it could be effective in bladder cancer, we believe it could be effective in kidney cancer.

“So there’s a lot of cancers where we think this vaccine can be effective.

“But we’re starting out with the two that we think have the highest probability of being effective and that is melanoma and lung cancer.”

Dr David Pinato, consultant medical oncologist at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, and investigator of the UK arm of the trial, told PA that cancer vaccines differ to immunotherapy, which also help the immune system “see” and attack cancer.

He said: “Current immunotherapies are removing the invisibility cloak that makes cancer hide within the body, but this removal is very non-specific.

“The appeal of cancer vaccines is that you can make it much more specific – you can basically give the immune system written instructions.

“It’s almost like an identikit of the tumour cells, which is more precise.”

He said the advantage of mRNA technology is that it “makes your own body produce those instructions”.

He added: “The fact your body is producing them awakens the immune system, it is even more active.”

He said the vaccine being tested in the trial is an “off-the-shelf vaccine” rather than one that is tailored to each individual patient.

While personalised vaccines can be very effective, they can take weeks to make and rely on a large tumour sample.

There is also not enough data at present to say whether personalised vaccines are in fact better than broader cancer vaccines, he said.

The Moderna vaccine, he added, is looking at specific traits across a number of tumours.

“It’s basically looking at what is the most frequent hit that you can target in cancer?,” he said.

“And so that has got incredible advantages in terms of the turnaround time, the fact you can make doses of the vaccines ahead of time even before meeting the patient. That is really the advantage.”

Dr Pinato said it is unclear why some patients benefit from immunotherapy and cancer vaccines while others do not.

“My educated guess, knowing what I know about cancer immunotherapy, is that the interaction between the tumour and the immune system is very complex,” he said.

For example, some types of lung cancer respond much better than others.

“It could be that maybe some patients cannot use those vaccines well, so the immune system is still so low it wouldn’t benefit, even with precise instructions,” he added.

“I think, having developed a number of drugs for cancer, there is never really going to be one that does everything.”

Professor Peter Johnson, NHS national clinical director for cancer, said the NHS “is at the vanguard of trials of cancer vaccines”.

He added: “We all know how worrying a cancer diagnosis can be for people and their loved ones, but access to these ground-breaking trials – alongside other innovations to diagnose and treat cancers earlier – provides hope, and we expect to see thousands more patients taking part in trials of this kind over the next few years.”

Health and Social Care Secretary Victoria Atkins said: “This vaccine has the potential to save even more lives while revolutionising the way in which we treat this terrible disease with therapies that are more effective and less toxic on the system.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel